READ: Are you being too Harsh or Permissive?

Managers often fall into the trap of being either too harsh or too permissive. Both of these traits are due to an imbalance in management style. The secret of effective management is to understand a number of paradoxes and the ability to balance two opposing behaviours.

Managers often fall into the trap of being either too harsh or too permissive. Both of these traits are due to an imbalance in management style. The secret of effective management is to understand a number of paradoxes and the ability to balance two opposing behaviours.

A number of my clients have been complaining that their managers are not keeping their eye on the ball, and letting performance slip through a lack of following up on the goals and objectives agreed with staff. I have also encountered a couple of organisations where there is a very strong culture of ‘compassion’ or ‘caring’ for service users; this means that many managers value ‘caring’ and want to ensure that they are ‘kind’ to their people. Addressing underperformance can feel harsh and uncaring, which creates a values conflict, especially when the managers believe that the only tool they have at their disposal is the disciplinary process. They are reluctant to use it because it feels far too harsh to address the issue at hand, and in many cases they are right. The disciplinary process is only to be used after you have had a number of informal but important conversations that firmly address the underperformance. However, it seems that many managers are reluctant to even give a reprimand or informal warning. They end up being permissive and this serves no one because standards drop, targets are not met and management will be seen to be ineffective. This can extend to the very top of an organisation.

I have also come across organisational cultures where there is a very firm line taken and any mistake or underperformance is dealt with very harshly. These businesses tend to suffer from a blame culture. It can also create high management and staff turnover because people want to feel that their line manager understands them and values them as a person. Harshness comes from a lack of warmth and empathy and if the manager is too harsh people often feel that they are being treated unfairly. It is interesting to note that neuroscientists have discovered that even a perceived lack of fairness triggers deep feelings of disgust in the brain and this can rapidly undermine working relationships and overall performance.

The paradoxes of good management

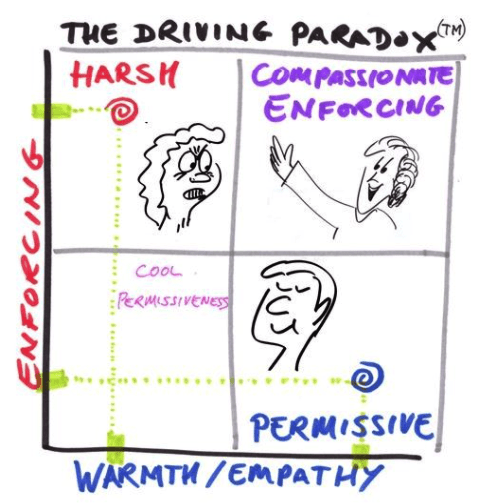

One of the paradoxes of good management is how to balance ‘Enforcing’ and ‘Warmth and Empathy’. ‘Enforcing’ is all about being able to ensure rules and standards are followed even when people don’t like it and may get defensive. ‘Warmth and Empathy’ is all about having an open heart and recognising the feelings of others.

These two traits may seem like oil and vinegar – they can’t mix and will always separate – but as any good cook knows, if you get them in the right balance they can create a great flavour and if you add a little emulsifier like egg yolk you get deliciously smooth French Dressing.

I’ve recently started working with a very interesting assessment tool developed by Dr. Dan Harrison.

His background in Mathematics, Personality Theory, Counselling and Organizational Psychology has enabled him to make a unique and exceptional contribution to assessment methodology.

One of the reports available illustrates a number of paradoxes. The ‘Driving’ Paradox is illustrated in the graph to the right. It shows that if you are high on ‘Enforcing’ and low on ‘Warmth and Empathy’ your behaviour will be ‘Harsh’, highlighted in red. If you are low on ‘Enforcing’ and high on ‘Warmth and Empathy’ you can become ‘Permissive’, highlighted in blue. The ideal balance is ‘Compassionate Enforcing’ which reminds me of the proverb: “Only a person with a kind heart can administer discipline that is beneficial to others”.

One of the reports available illustrates a number of paradoxes. The ‘Driving’ Paradox is illustrated in the graph to the right. It shows that if you are high on ‘Enforcing’ and low on ‘Warmth and Empathy’ your behaviour will be ‘Harsh’, highlighted in red. If you are low on ‘Enforcing’ and high on ‘Warmth and Empathy’ you can become ‘Permissive’, highlighted in blue. The ideal balance is ‘Compassionate Enforcing’ which reminds me of the proverb: “Only a person with a kind heart can administer discipline that is beneficial to others”.

However, any imbalance can also cause a ‘Flip’ when a manager is under stress. So the Permissive Manager can suddenly become ‘Harsh’ (“I’ve given you lots of chances and now you are going to see what happens when you take advantage of me . . .”). The Harsh Manager can fall into avoiding the final difficult conversation and lead people to think that their “Bark is worse than their bite”, so they get used to the harshness and continue to underperform, because there is no ultimate consequence.

Gain respect

There is now plenty of scientific evidence from recent psychological studies that show how ‘Compassionate Enforcing’ is highly respected by people because it is perceived as fair and just. This means that it avoids triggering defensive mechanisms that can be generated deep in our reptilian brain. Once defensiveness is triggered, rational behaviour goes out of the window, and people start thinking negatively and taking things very personally. This is always far more difficult to manage.

It is interesting to note that being low on both of these traits leads to ‘Cool Permissiveness’ which is very ineffective. The studies show that it leads to people having a lack of respect for their manager and treating them with a sense of pity and disgust.

Making a shift

When I drew this graph on a flip chart on a recent management development course with the caring managers it became clear to many of them that they needed to keep the same levels of ‘Warmth and Empathy’ while increasing the level of ‘Enforcing’. This meant making a shift in their perception and recognising that being ‘Permissive’ was not serving the organisation, its end users or the staff.

The concept behind these Paradoxes is the need to understand the principles of the opposing traits and exercise more of both. It is not about doing less of what you naturally prefer; it is about looking at any imbalances and learning ways to improve the balance between them. This can be achieved by greater self-awareness, being open to feedback and a willingness to improve.

If you are interested in exploring where you and your managers stand on this Paradox and the eleven other Paradoxes in the assessment please contact us at info@talent4performance.co.uk

Check out the 150-second Food for Thought video episode on the Paradox of Driving Performance LinkedIn:

https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6473181578385244160/

Remember . . . stay curious!

David Klaasen

©David Klaasen – May 2016